I take a deep breath and say that I know I am a work in progress. I need to build strength and understanding in order to stay on the road of being a wildlife volunteer.

I had the warning notification on my FiresNearMe app on the phone as I was getting ready for bed. An alert for a fire which was 5kms away from home. All ok in the end but try telling that to already primed reactions.

The fire alert took me straight back to the 2020 summer. The same feelings and immediate physical reactions started again; tensing and stomach churning, shorter, very shallow breathing. The mind going a gazillion miles an hour. A reminder of a state of hyper-readiness which was forever on alert, for too long, for too many people. A state which won’t recognise the difference between actual and perceived threats.

As I experienced these emotions and physical sensations, I recalled what I had learnt about the ‘Neurobiology of the Brain’. I see this as a fancy term for understanding how the brain works. I’ve been seeking this out because I know I am still unsettled by the events of Spring/Summer 2019-2020, and I wanted to understand more about the interlinkage between what I was thinking and feeling. I don’t mind admitting I need to see a professional, it was a traumatic period and there is some stuff I need to work through. The bushfires are no longer in the news, but for many that has not lessened the experience or impact.

What were the comforting, learning points I read about how the brain worked in trauma? As someone without any formal psychological training, these three learnings resonated, and really helped me appreciate how my wildlife volunteer role permeates my whole being.

- The strength of the body’s automatic internal reactions.

- The heightened capacity for self-talk.

- Why logic and reason evaporates at times of stress.

At times of stress, trauma and uncertainty, our bodies have internal actions that may be triggered without our awareness. These triggered states may stay on, even when the threat is perceived and not real. Understanding that sometimes we need to invest in actions to calm our body, so that we can decide whether to take action on the source of the stress or uncertainty, was a big learning for me.

Our wildlife volunteer work can expose us to situations where we see trauma. This may be at an individual rescue/euthanise animal level or larger scale wildlife circumstances such as bat heat stress events or bushfires. I have learned our exposure or experience of trauma may mean that we have a tendency to self-blame. For example, “I should have done more. If I had then more wildlife could have been saved.” Or we blame our stress symptoms “Why can’t I sleep – other people have been through hell, I’ve not lost my house or property, why am I so jumpy and on edge? Why do I cry so easily? It’s because I am hopeless and weird.” For me these downward spirals of self-talk further fuel a feeling of helplessness and paralysis.

Now that I know that this heightened capacity for self-blame, my harsh internal response is becoming softened. I now understand that this is what the brain does when it is exposed to events that are overwhelming. It gave me permission to recognise the self-talk and provide enough distance so that I can observe what I am saying, but I don’t have to believe it. Sounds simple, but it is really hard and I am still a work in progress.

When chatting with a friend she added a bit more to this self-talk cycle that I found helpful. She said to notice the self-talk, name it (what value or important thing does it refer to) and neutralise it by creating actions to ‘move’ rather than judge.

Notice: ‘I’m stupid because I can’t get anything done’ – hear these words;

Name: I am needing to achieve something, anything; and

Neutralise: OK, small steps to achieve a small task – one thing at a time. Choose an action.

These steps are expressed in a slightly different way here as another reference.

I had a conversation with someone who was doing everything possible to give out grants at the height of the bushfires, including sitting with a person to help write the words for what was a simple application. Forms, decisions, prioritising, planning, concentrating, and thinking about the future, are all examples of day to day things that are very difficult when in survival mode. Knowing this gave me a lightbulb moment of relief as I had told myself that ‘I was going crazy’ or ‘I’m stupid because I can’t get anything done’. It turns out when we experience trauma that there are physical processes within the body and brain which lead to the logic-based part of the brain shutting down.

It has helped bring a level of awareness that sometimes myself or others around me who have experienced trauma, may not be in the best state to work through things logically and that may be influencing our reactions and interchanges with one another. It has heightened for me the importance of working in teams and why its ok to reach others to others to for help. There are situations where I am nutting through a complex problem with a wildlife charge in care where I need to ask for help from someone else’s not-stressed logical brain, that functioning better than mine at that point.

I have become more aware that stress is both a physiological and psychological reaction that is activated when we are confronted by a challenging situation. A simple statement that hides the fact that for so long I lived with the thought that stress was merely an emotional thing.

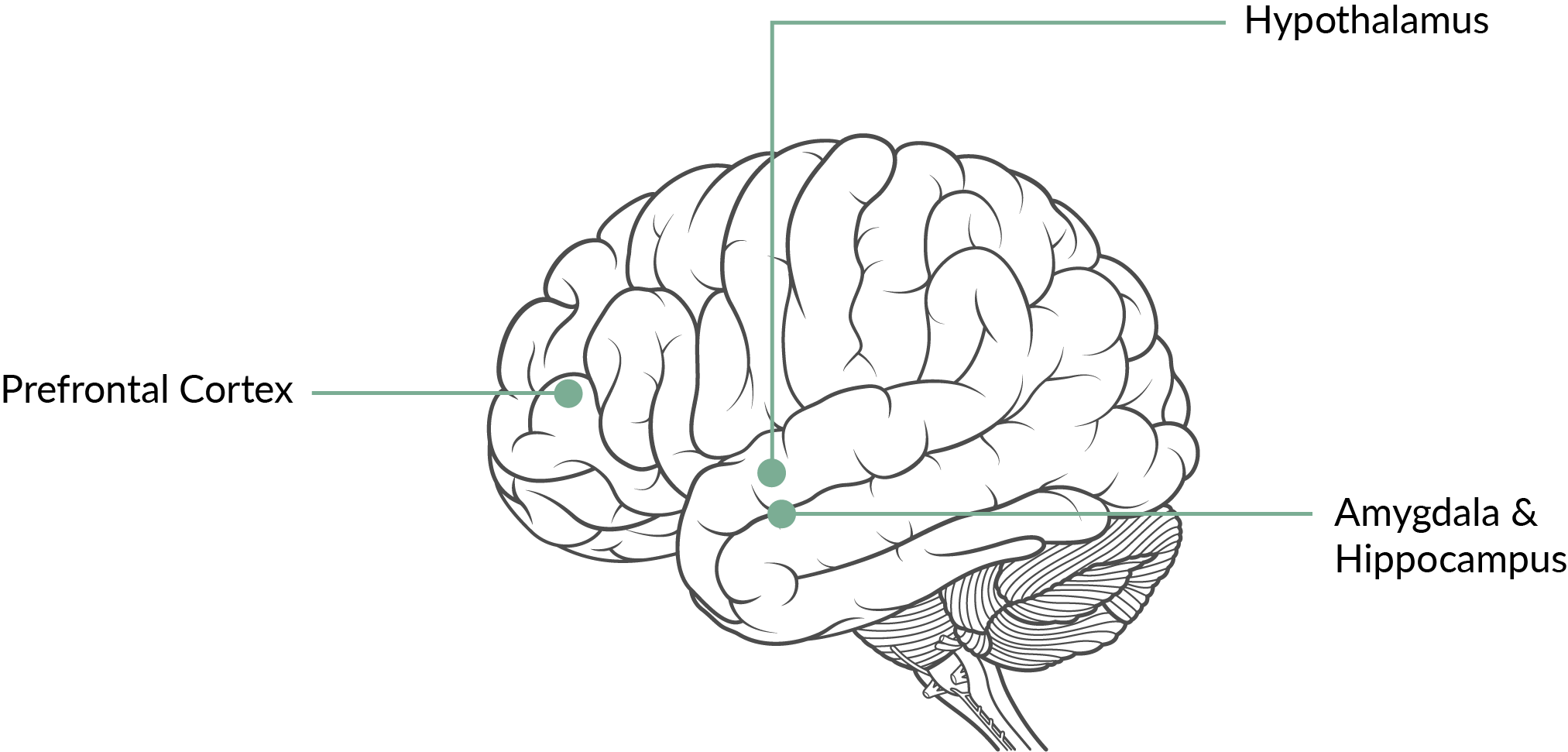

The Limbic System in our brain is where our emotional reaction to stress takes place, it is here that our fight, flight or freeze response is activated. The image below shares the components of the Limbic System that help us process stress:

Amygdala and Hippocampus

If something is seen as a stressor, the Amygdala triggers the Flight – Fight – Freeze response in the brain. It then tells the Hippocampus to remember everything about it, shaping our future response to similar events.

Hypothalamus

After the Amygdala triggers the Flight – Fight – Freeze response, the hypothalamus carries it out. It sends a message to your adrenal glands to release adrenaline and cortisol. Cortisol is a hormone that causes stress reactions throughout the body. If you’re constantly in a fight, flight or freeze state, these hormones can do damage to your body.

Prefrontal Cortex

While not part of the limbic system, the prefrontal cortex has a close relationship with how we experience stress. When something happens, information gets sent here for us to process the event on a more intellectual level – with logic and evaluation skills. Using those, we develop a response, however stress can disrupt the prefrontal cortex, making it harder to make access a logical space to make decisions and problem solve.

Source: How Your Brain Processes Stress

I am incredibly grateful nature has provided consistent and very welcome rain since those terrible dry hot months. There is something psychological that happens when you see green rather than a constant palette of browns or just black. The green relief, the tiny micro steps of nature healing, provides me with hope and healing.

The time gap since the fires has given me a chance to learn what my brain and body have been doing, my default capacity of negative self talk and that there will be situations where my logic system is offline and I will need to draw on help from others. That’s ok. This reflection was sparked by contemplation of a large scale event, the memory of which is still large. There are automatic and unseen body/brain processes that I know are also triggered by situations I experience as part of my every day wildlife volunteer journey. We are always learning and I know I am a work I progress…

Take some time to Refill Your Bucket:

It’s great to have annual markers as gentle reminders to check in with ourselves and our mental wellbeing. Our mental health can ebb and flow, and for those of us wildlife volunteer sector, it is okay to say that we are a work in progress.

Our FREE 5-part email series is aimed at helping to acknowledge meaningful steps towards understanding and refilling your bucket. Such reflections help us to build awareness, strength, and healing.

Email 1: How do we build awareness of our bucket?

Email 2: Why self-sustainment makes sense?

Email 3: What is our stress awareness like?

Email 4: Are we hearing and understanding our body signals and reactions?

Email 5: Why joy is important for filling our buckets.